Friday, May 11, 2012

What was The Protestant Reformation?

The Protestant Reformation changed religious attitudes

Around 1500 a number of northern humanists were suggesting that the Church had lost sight of the spiritual mission proclaimed by Jesus himself. Instead of setting an example of moral leadership, they said, popes were becoming political leaders and warriors. Instead of encouraging inner piety, priests were concerned about the details of ceremonies. And the Church as a whole, they said, seemed more interested in its income than in salvation. What the northern humanists were seeking was a new emphasis on personal faith and spirituality. When their message went unheard in the Church, a new generation of reformers urged believers who were unhappy with official religion to join a new church. This religious revolution, which split the Church in Western Europe, is called the Reformation.

George Herbert

|

| George Herbert (1593-1633) |

Herbert was born into a noble Welsh family. Ordained about 1626, he gave up a career at court and at Cambridge University to become a devoted parish priest, from 1630 to his death.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

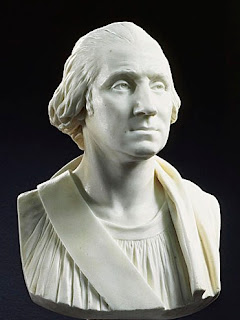

Jean Antoine Houdon

Jean Antoine Houdon (1740-1828) was the greatest French sculptor of his day, was born at Versailles. He began work in his art at a very early age, and at twenty won the coveted Prix de Rome. Houdon studied in Rome for ten years, at the end of which he returned to Paris as instructor at the School of Fine Arts. Among his finest works are the busts of Catherine II, Moliere, Rousseau, Voltaire, Buffon, Lafayette, Napoleon, Franklin and Washington. To make the latter, which is now in the state capitol of Richmond, Va., Houdon accompanied Franklin to the United States in 1785. It is considered the finest likeness of Washington extant.

Bust of Washington (Houdon)

Did you know that...

Did you know that...

as many as 250,000 new nerve cells can be formed each minute during a baby's development inside its mother? By the time the baby is born, the brain will have almost all the nerve cells, or neurons, it will ever nave. However, a child's brain continúes to increase in size after birth as other brain cells, called glia, grow around the neurons, insulating them and carrying out various "housekeeping" functions in the brain. A baby is also born with trillions of connections, or synapses, be-tween neurons. As the child learns various skills, many of these synapses are stimulated and become permanent connections.

Christopher Columbus

Even before Vasco da Gama brought wealth to Portugal, Spain also had become interested in the search for new trade routes. Its rulers, Ferdinand and Isabella, decided to finance a voyage by Christopher Columbus, an Italian navigator. Thinking that the world was much smaller than it actually is, Columbus believed he could reach India quickly and easily by sailing westward.

In August 1492 Columbus set sail with three small ships from Spain and crossed the Atlantic. His small fleet landed in October on a tiny island in the Caribbean Sea. He named the island San Salvador. After visiting several other islands, Columbus returned triumphantly to Spain in the spring of 1493 to report his discoveries. He believed the islands to be off the coast of India and therefore called their inhabitants "Indians." Actually, he had discovered the islands later known as the West Indies. Although Columbus made three more voyages between 1493 and 1504, he believed until his death that the lands he had found were part of Asia.

Romance languages

A Romance language is any of several languages that developed from Latin. The Romance tongues include French, Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian. Other Romance, or Romanic, languages are Sardinian and Rhaeto-Romance (the general name for a group of languages, including Romansh, spoken in certain parts of Switzerland, the Tyrol, and Friuli).

The Romance group also includes Provençal, the language spoken in southern France. Provençal was the language of the troubadours, who were the poets of the 1100's. The lyrics of more than 400 Provençal poets have come down to us. Most of their poems were love lyrics, but some had moral, religious, or political themes written to popular melodies. The use of Provençal as a literary medium began to decline soon after A. D. 1200.

Romance languages grew up because Rome sent colonists to settle the countries it had conquered. The soldiers, tradesmen, and farmers who colonized these conquered countries took their language with them, but it was not the Latin of the classics studied in school today. It was popular, or vulgar, Latin, the everyday speech of ordinary people. This popular Latin often adopted words or features of pronunciation from the language of the conquered country. For example, the Latin word for hundred, centum, became cent in French, ciento in Spanish, and cento in Italian. The varieties of popular Latin formed in this way eventually developed into separate languages.

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Why were some of the early bridges in the United States covered?

Covered bridges once dotted the American countryside from the Atlantic Coast to the Ohio River. The bridges looked like square tunnels with peaked roofs. Some people claim that the bridges were cov¬ered so that horses would not be frightened by the water underneath. Others say that they were built as a shelter for travelers in faad weather. Actually the coverings were designed to protect the wooden framework and fiooring of the bridges and keep them from rotting. The pitched roofs, which shed snow, also reduced the amount of heavy snow that collected on the bridges. Wooden bridges became obsolete as traffic loads increased and modern trucks grew in size. Today only a few are still stand-ing. Many people work to preserve the remaining covered bridges.

Realism and Perspective in Giotto's art

The changes in painting from medieval to modern times can be seen in the work of the great early Renaissance artist Giotto. In this painting the angel of God tells St. Anne that she will have a child, Mary, who will be the mother of Jesus. There is a three-dimensional quality in the lighted room, in the rooftops that recede into the dark, and in the faces of the women and the angel. Thus Giotto makes us feel the scene is an actual event rather than a symbolic one.

Giotto was an architect as well as an artist. His interest in architectural detail and perspective heighten the realism of his work. Like other Renaissance artists, he was interested in showing a building or a landscape as it appeared through a person's own eyes. Later Renais¬sance painters developed perspective mathematically and were able to portray distances with great accuracy.

Giotto was an architect as well as an artist. His interest in architectural detail and perspective heighten the realism of his work. Like other Renaissance artists, he was interested in showing a building or a landscape as it appeared through a person's own eyes. Later Renais¬sance painters developed perspective mathematically and were able to portray distances with great accuracy.

What is Horsepower?

Horsepower is literally the power of a horse or the rate at which it can perform work. With the invention of the steam-engine, it became necessary for Watt to express its power in terms of the horse, and the standard he established has been generally adopted. So the horsepower became equivalent to the raising of thirty-three thousand pounds one foot high in one min¬ute, or to the doing of work at the rate of thirty-three thousand foot pounds per min¬ute. This somewhat exceeds the activity of an average horse except for limited periods. The determination of the horsepower of a steam-engine is a comparatively simple matter. Multiply together the area of the piston in square inches, the length of the stroke in feet, the mean effective pressure of the steam in pounds per square inch, and the number of strokes per minute, and di¬vide the product by thirty-three thousand. It is customary to subtract ten percent for friction.

The unit of power in metric units is the watt, named from the inventor, and is equal to doing work at the rate of one joule, or ten million ergs, per second. The kilowatt is of more practical size, and equals one and one-third horsepower.

The unit of power in metric units is the watt, named from the inventor, and is equal to doing work at the rate of one joule, or ten million ergs, per second. The kilowatt is of more practical size, and equals one and one-third horsepower.

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Is it true that we use only 10 percent of our brains?

No. This is a common misconception. Although different parts of the brain are more or less active during different activities, there is no evidence that we use only a small portion of our brains. Damage to a small area of the brain can cause devastating effects, such as amnesia, paralysis, or loss of language. This suggests that every part of the brain serves an important function, upon which other parts of the brain depend.

On the other hand, some people— especially children—can recover after suffering major damage to the brain or even losing part of it. Such remarkable recoveries do not suggest that we need only a fraction of our brain, however. Rather, they illustrate the tremendous capacity of the brain to "rewire" itself: Cells in the remaining parts of the brain form new connections and take over the functions of those parts that were removed.

On the other hand, some people— especially children—can recover after suffering major damage to the brain or even losing part of it. Such remarkable recoveries do not suggest that we need only a fraction of our brain, however. Rather, they illustrate the tremendous capacity of the brain to "rewire" itself: Cells in the remaining parts of the brain form new connections and take over the functions of those parts that were removed.

Frederick the Great

Frederick William I had a real worry as he nearer the end of his life. His son had little interest in either military life or government service. Instead, he spent his time writing poetry, playing the flute, and reading philosophy. The king used the harshest methods, even imprisonment to force his heir to be more nearly the son he desired.

As it turned out, Frederick William's son proved to be an even stronger ruler than his father. He turned out to be one of Prussia's great¬est military and political leaders and is known Frederick the Great.

Frederick William's son took the throne of Prussia as Frederick II in 1740, the same year in which Maria Theresa became ruler of Austria. He was a skilled administrator, who instituted social reforms and began work on a Prussian law code. Like his grandfather, he admired French culture He also wrote several books, including a history of Brandenburg and a book on the duties of rulers.

As it turned out, Frederick William's son proved to be an even stronger ruler than his father. He turned out to be one of Prussia's great¬est military and political leaders and is known Frederick the Great.

Frederick William's son took the throne of Prussia as Frederick II in 1740, the same year in which Maria Theresa became ruler of Austria. He was a skilled administrator, who instituted social reforms and began work on a Prussian law code. Like his grandfather, he admired French culture He also wrote several books, including a history of Brandenburg and a book on the duties of rulers.

Victor Herbert

Victor Herbert (1859-1924) was an American composer and conductor, is often called "the prince of operetta." One of his most famous operettas is Babes in Toyland (1903), which was based on Mother Goose and fairyland characters. "March of the Toys" and "Toy¬land" are well-loved numbers in this operetta. He also wrote Mlle. Modiste (1905), which includes the popular song "Kiss Me Again." Naughty Marietta (1910), one of the most tuneful of his operettas, in¬cludes such songs as "Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life," "I'm Falling in Love with Someone," "Italian Street Song," and " 'Neath the Southern Moon."

Herbert was born on Feb. 1, 1859, in Dublin, Ireland, of a musical family. He studied the cello in Ger¬many, and played in leading European orchestras. In 1886, he settled in New York City, where he played cello in the Metropolitan Opera Company Orchestra. In 1893, Herbert followed Patrick S. Gilmore as bandmaster of the Twenty-second Regiment Band. He wrote his first operetta, Prince Ananias, in 1894. It was not a great success, but The Wizard of the Nile, a year later, proved a major success.

Read more »

Herbert was born on Feb. 1, 1859, in Dublin, Ireland, of a musical family. He studied the cello in Ger¬many, and played in leading European orchestras. In 1886, he settled in New York City, where he played cello in the Metropolitan Opera Company Orchestra. In 1893, Herbert followed Patrick S. Gilmore as bandmaster of the Twenty-second Regiment Band. He wrote his first operetta, Prince Ananias, in 1894. It was not a great success, but The Wizard of the Nile, a year later, proved a major success.

Read more »

Monday, May 7, 2012

Did you know that . . .

Some 650 muscles cover the body's skeleton? Muscles do more than shape and define the contours of our bodies. They are responsible for all of the body's movements. Muscles are attached to bones by tough, hard tissue called tendons. In response to instructions from the brain, muscles contract and pull on the bones and movement occurs. Usually skeletal muscles work in groups. Even aseemingly simple task such as taking one step involves about 200 muscles! Some muscles lift and move your leg forward, while others in the back, chest, and abdomen help keep you from losing your balance during the motion.

Leather

Of all the ancient industries that of the manufacture of leather is one of the most interesting on account of the convertibility of an easily descomposed substance into one which resists putrefaction. The manufacture of leather is as old as history itself. In China the manufacture and use of leather was known before the Christian era, and in Egypt leather has been found in mausoleums of the ancients, showing us that rations in the remote ages of the past were practised in the art and left slight traces of their high civilization to be admired today. The Persians and Babylonians passed the art over the Greeks and Romans and so down through the different medieval nations to us. The Amer¬ican Indians were also well versed in the art of making leather. Although their method of tanning was entirely different from that of the ancient races, the fact remains that they also discovered a way of treating the skins of animals in such a way as to prevent the putrefaction of animal tissues.

Money in history

In early times any object that everyone accepted as valuable could serve as money. The Romans, for example, paid their soldiers with what was then a prized commodity, salt. From this custom we get the phrase, "worth ore's salt." Other items that have been used as money include shells, tobacco, feathers, and whale teeth.

Probably the first money made specifically as a medium of exchange appeared in China during the Shang dynasty. Because farmers often had traded spades and knives for other goods, this ancient money was shaped like spades.

Increasingly, rare metals, especially gold and silver, came to be used as money. They were fashioned into coins, which could be carried easily. Governments jealously guarded the right to make coins and to establish their value. Often, however, government officials would clip pieces off coins. Then they would melt these down to make more coins so that they could buy more. During the 1500's this process brought on inflation and was stopped only when milled, or grooved, edges were put on coins. This enabled people to see at once if the coins had been clipped.

About this time, too, paper money became more common. The Chinese, the first to use both paper and movable type, were also the first to use paper money, about the year 1060 A. D. Paper money was even more convenient than coins and became especially useful as long-distance trade grew increasingly important.

Probably the first money made specifically as a medium of exchange appeared in China during the Shang dynasty. Because farmers often had traded spades and knives for other goods, this ancient money was shaped like spades.

|

| coin |

About this time, too, paper money became more common. The Chinese, the first to use both paper and movable type, were also the first to use paper money, about the year 1060 A. D. Paper money was even more convenient than coins and became especially useful as long-distance trade grew increasingly important.

Sunday, May 6, 2012

Who were the Hesperides?

In Greek mythology, the Hesperides were the daughters of Atlas and Hesperus (Evening). They lived at the western end of the world. They guarded the golden apples which Gaea (Earth) gave to Hera when she married Zeus. A sleepless dragon helped them. One of Hercules' labors was to steal these apples.

Hesperides

Iron

Iron is a hard, heavy, well known metal. Pure iron is silvery-white in color, but it is seldom seen. Wrought iron is the purest commercial form; yet piano strings, the purest wrought iron in the market, contain three pounds to the thousand of carbon and other elements. When in the presence of a magnet, or when placed with-in a coil through which an electric current is passing, soft iron becomes magnetic. Iron remains unchanged in dry air, but rusts —unites with oxygen—in moist air.

Iron is the most useful of all metals, and of all metals it is the most widely distributed in nature. It forms a twentieth part of the world's crust. It is essential to life of all sorts. It is found in the green chlorophyll of plants and in the blood of ani¬mals. It occurs in meteorites. The color spectrum shows that iron is present in the Sun. There is an iron mountain near Durango, Mexico. It is a projecting back-bone or dike of solid iron ore,—a huge mass one mile long, a third of a mile wide, and 450 to 650 feet high. Similar hills in Missouri are known as Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob.

Iron is the most useful of all metals, and of all metals it is the most widely distributed in nature. It forms a twentieth part of the world's crust. It is essential to life of all sorts. It is found in the green chlorophyll of plants and in the blood of ani¬mals. It occurs in meteorites. The color spectrum shows that iron is present in the Sun. There is an iron mountain near Durango, Mexico. It is a projecting back-bone or dike of solid iron ore,—a huge mass one mile long, a third of a mile wide, and 450 to 650 feet high. Similar hills in Missouri are known as Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob.

Iron meteorite

Saturday, May 5, 2012

What was the Fries Rebellion?

The Fries Rebellion was an uprising in eastern Pennsylvania in 1799, led by John Fries (1764-1825). By act of July 14, 1798, Congress imposed a direct tax of $2,000,000, which was to be equitably apportioned among the various states and which was laid upon all dwelling houses and lands, and on slaves between the ages of 12 and 50. The value of the dwelling houses was to be determined on the basis of the size and number of Windows in these houses, and an impression thus got abroad that citizens who owned houses were being taxed for having Windows, the tax thus coming to be known in some communities as a "window tax." In the eastern counties of Pennsylvania (Northampton, Bucks, Montgomery, Lehigh and Berks), the large German element vigorously opposed the tax, and under the leadership of Fries, resisted by force (March, 1799) the Federal officers sent to measure Windows preparatory to assessing the owners of dwelling houses.

Riots soon broke out; some 30 of the rioters were arrested; and at Bethlehem these arrested rioters were rescued by their associates led by Fries. President Adams issued a proclamation against the rioters, troops were called out, and the disturbances were quickly suppressed. Fries was arrested, was tried on a charge of treason—the first trial of the sort in the history of the United States—and was convicted (1799). A new trial, however, was granted, but in the following year Fries was again convicted and was sentenced to the gallows. It was partly for the high-handed manner in which Judge Chase conducted this trial that he was impeached by the House and tried before the Senate. Fries was pardoned by President Adams, and subsequently became a prosperous dealer in tinware in the city of Philadelphia.

Friday, May 4, 2012

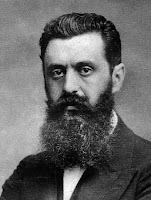

Who was Theodor Herzl?

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) was an Austrian journalist and playwright who founded the Zionist movement. The aim of this movement was to set up a Jewish national home in Palestine. Herzl was born in Budapest, Hungary, and studied law at the University of Vienna.

The growing problem of anti-Jewish feeling in Europe, increased by the Dreyfus case in France, attracted Herzl's attention. He saw that European Jews had failed to gain social equality even when they had become politically free. So Herzl got the idea of gathering the scattered Jews into a country and a nation of their own. His motives were economic and social, rather than religious. Herzl's Jewish State, pub¬lished in 1896, attracted many persons to this cause.

Max Nordau and Israel Zangwill were among them. Herzl kept up contact with the leaders of many nations. In 1897, he presided over the first Zionist congress in Basel, Switzerland. In 1901, Great Britain offered the Jewish people land in British East Africa. Worry about the dispute over this offer injured Herzl's health and hastened his death.

The growing problem of anti-Jewish feeling in Europe, increased by the Dreyfus case in France, attracted Herzl's attention. He saw that European Jews had failed to gain social equality even when they had become politically free. So Herzl got the idea of gathering the scattered Jews into a country and a nation of their own. His motives were economic and social, rather than religious. Herzl's Jewish State, pub¬lished in 1896, attracted many persons to this cause.

Max Nordau and Israel Zangwill were among them. Herzl kept up contact with the leaders of many nations. In 1897, he presided over the first Zionist congress in Basel, Switzerland. In 1901, Great Britain offered the Jewish people land in British East Africa. Worry about the dispute over this offer injured Herzl's health and hastened his death.

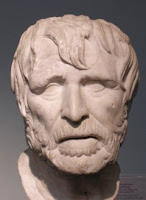

Hesiod (Greek poet)

HESIOD (700's B.C.), was the first major Greek poet after Homer. He was the first poet to write didactic (instructional) poetry, and the first to reveal his personality through his poetry.

His major work, Works and Days, is addressed to his brother Perses. In it, Hesiod speaks of his town of Ascra in Boeotia as being "cold in winter, hot in summer, and pleasant at no time." Instead of glorifying warrior heroes as Homer did, Hesiod advocated hard work, frugality, and prudence. Works and Days includes practical advice on how to live and farm, and specifies dates on which certain tasks ought to be done. It also contains a story of the fall of man through Pandora's untimely curiosity. It describes the deterioration of the world through five stages: the Age of Gold; the Silver Age; the Bronze Age; the Age of Heroes; and the Age of Iron. Hesiod lived in the Age of Iron. Another work believed to be Hesiod's is Theogony. In it, he tried to solve conflicting accounts of the Greek gods and their functions.

His major work, Works and Days, is addressed to his brother Perses. In it, Hesiod speaks of his town of Ascra in Boeotia as being "cold in winter, hot in summer, and pleasant at no time." Instead of glorifying warrior heroes as Homer did, Hesiod advocated hard work, frugality, and prudence. Works and Days includes practical advice on how to live and farm, and specifies dates on which certain tasks ought to be done. It also contains a story of the fall of man through Pandora's untimely curiosity. It describes the deterioration of the world through five stages: the Age of Gold; the Silver Age; the Bronze Age; the Age of Heroes; and the Age of Iron. Hesiod lived in the Age of Iron. Another work believed to be Hesiod's is Theogony. In it, he tried to solve conflicting accounts of the Greek gods and their functions.

What is water gas?

Water Gas is a colorless gas that burns with a hot, blue flame. Water in the form of steam is passed over red-hot coke, forming hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The hydrogen and carbon monoxide are then passed through a retort in which carbonaceous matter such as resin is undergoing decomposition absorbing therefrom sufficient car¬bon to render it luminous when burned. The average composition of water gas is approximately: carbon monoxide, 40-50 percent; hydrogen, 45-50 percent; carbon di¬oxide, 3-7 percent; nitrogen, 4-5 percent.

Thursday, May 3, 2012

Car improvements

Since the 19th century the automobile it developed quite fast. Between World Wars I and II and ever since, improvements have continued to come along. Let's take a quick look at some of these improvements and when they happened. In 1906 front bumpers were added, but it was not until 1915 that tops and windshields became standard equipment on all American cars. A year later rear-view mirrors, stoplights, and an early form of windshield wiper came along. In 1923, four-wheel brakes were introduced, and 3 years later the first automobile heaters were added. By 1927, hydraulic brakes had replaced mechanical brakes, and in 1929 the first car radios were introduced along with dimmers for headlights. In 1937 the gearshift lever was moved to the steering column. That same year saw the introduction of the first automatic transmission. After the war ended, power steering was invented and wrap-around windshields were added for better vision. In the early 1960's seat belts were introduced for safety.

Water bath

Water Bath is a bath of fresh or salt water, as distinguished from a vapor bath. In chemistry, a copper vessel, having the upper cover perforated with circular openings from two to three inches in diameter. When in use it is nearly filled with water, which is kept boiling by means of a gas burner, and the metallic or porcelain basin containing the liquid intended to be evaporated is placed over the openings mentioned above.

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Waterfall

Waterfall, or Cataract, is the fall or per-pendicular descent of water from a stream or river, found mostly in mountainous regions. It is usually the result of a geológi¬ca! upheaval in which ¡mínense masses of rock were shifted hundreds of feet from their former position. In geologic time whole areas were thus elevated and others depressed, and in favorable locations where the fault was abrupt, waterfalls were formed. Subsequent changes resulted from erosion of rocks of different hardness. A remarkable series of waterfalls exists along the inward edge of the Atlantic coastal plain, in the neighborhood of the cities that lie between Trenton, N. J., and Augusta, Ga. Mountain cataracts or cascades make the highest waterfalls. Some of the most important waterfalls and cataracts are: The Falls of Yosemite in California, over 2,500 feet, the highest in the world; the Oroco Falls at Monte Rosa, Switzerland. over 2,000 feet; Victoria Falls in Africa, over 420 feet; Niagara Falls, 165 feet, and Iguassu Falls on the Iguassu River, which separates Argentina and Brazil. In high water the Iguassu Falls are greater in volume than Niagara Falls and are much greater both in height and width; the Gavarnie Falls in the Pyrenees are 1,385 feet; and the Staubbach Falls, Switzerland, 908 feet. Other celebrated waterfalls of the world are: Bridal Veil, Yosemite Park, 620 feet; Chamberlain, British Guiana, 300 feet; Fairy, Rainier Park, 700 feet; Gersoppa, India, 830 feet; Granite, Rainier Park, 350 feet; Illilouette, Yosemite Park, 370 feet; Kalambo, South Africa, 1,400 feet; Multnomah, Oregon, 850 feet; Nevada, Yosemite Park, 594 feet; Ribbon, Yosemite Park, 1,612 feet; Rjukan, Norway, 780 feet; Roraima, British Guiana, 1,500 feet; Skjaeggedalsfos, Norway, 530 feet; Sluiskin, Rainier Park, 1,300 feet; Sutherland, New Zealand 1,904 feet; Takkakaw, British Columbia, 1,200 feet; Vettis, Norway, 950 feet; Voringfos, Norway, 600 feet; Wid-dows' Tears, Yosemite Park, 1,170 feet.

What is a houseboat?

A houseboat is a combination of a boat and a house. Taking a hint from the boat dwellings of eastern Asia, or possibly from the canal boat, the English originated the pleasure houseboat during the nineteenth century. It is a broad, commodious, comfortable affair, consisting of one or more rooms on a flat boat of shallow draft. It is quite popular on the Thames for families or small pleasure parties. The houseboat has been introduced into America. Long Island Sound and the Hudson, the St. Lawrence, the Ohio, the Mississippi, and other American rivers have their fleets of houseboats, which are brought into requisition during the summer months.

What is a Hourglass?

The hourglass is a contrivance for measuring time. In making, the glass-blower closes a cylinder at each end, and draws the walls together to form a small passage or waist at the middle. When complete the glass has the form of two cones placed point to point. In use, as much sand or mercury is inclosed in one end as will run through the passage in an hour. By turning the glass the other end up, the passage of another hour can be marked, and so on. If a person were set to do a task, or wished to speak for an hour, the hourglass reminded him of the passage of time, and also when his "hour was up." Its use gave rise to the expression, "the sands of time." The hourglass continued in use for a long time after the invention of clocks.

Water lily

The water lily is an aquatic perennial belonging to the Nymphacaceae family and including the genera Nyphaea and Nuphar. The water lilies are characterized by a thick fleshy rootstock or tuber which is usually embedded in the muddy bottom of the shallow pond; by large shield-like floating leaves; and by conspicuous ornamental flowers. The flowers are often fragrant and possess beautiful waxy petals. There is a wide range of flower color, white, yellow, rose, red, blue and bronze. The flowers bloom either during the day or night. They include a few outstanding forms such as the lotus flower of Egypt, India and China and the giant water lily, Victoria regia, which grows in the backwaters of the Amazon. The flower of the latter is a foot wide and the leaves are 6-7 feet wide.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

The Man with the Iron Mask

|

| Iron mask |

What is isinglass?

|

| isinglass sheet |

Monday, April 30, 2012

What is the harvest moon?

Harvest Moon is the full moon that occurs nearest the date of the autumnal equinox, September 22. Since this is harvest time, the name harvest moon has become general. At this time of year the moon is traveling at the least possible angle with the ecliptic, and rises at about the same time on several successive nights, and shines with unusual brilliance. While the harvest moon has often been the inspiration of poet and painter, it also serves the practical purpose of furnishing the agriculturist with light strong enough to work by at the season when time is precious.

Sunday, April 29, 2012

Antibiotics in the 20th century

Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928. Penicillin stopped the growth of disease-carrying bacteria. Thus it could help cure illnesses caused by these bacteria. In the years after Fleming's discovery, other substances were discovered to have similar effects. Streptomycin, which was discovered in 1944, attacked bacteria that could resist penicillin. All of these substances are called antibiotics, and after 1945 they transformed the fight against disease. They cured certain illnesses, such as tuberculosis, that previously could not be treated, and they made surgery safer from infections. Antibiotics were also used to improve the health of animals that are used for food. Although some bacteria came to resist antibiotics, these substances became essential in reducing sicknesses and providing more food.

What is homeopathy?

HOMEOPATHY is a system of medical practice based on a theory of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann of Leipzig. He practiced this system about the beginning of the 1800's. He called it homeopathic to distinguish it from the older school of medicine, which he called allopathic.

Hahnemann's theory was that a drug which will pro-duce certain disease symptoms in a healthy person will cure a sick person who has the same symptoms. He expressed this in the Latin phrase, Similia similibus curantur, which means like cures like.

In spite of opposition by the leading physicians of his day, Hahnemann became noted and had many followers. Homeopathic medical schools, clinics, societies, and journals sprang up in various cities in Europe and the United States.

Hahnemann's theory was that a drug which will pro-duce certain disease symptoms in a healthy person will cure a sick person who has the same symptoms. He expressed this in the Latin phrase, Similia similibus curantur, which means like cures like.

In spite of opposition by the leading physicians of his day, Hahnemann became noted and had many followers. Homeopathic medical schools, clinics, societies, and journals sprang up in various cities in Europe and the United States.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (1831-1885) was an American writer. Her maiden name was Helen Fiske. She was born at Amherst, and died at San Francisco. In 1853 she married Captain Edward Hunt, with whom she traveled extensively in the West, gathering the material afterward used in her stories and poems. In 1863 Captain Hunt died. Her second husband, W. S. Jack¬son, was a banker. She adopted "H. H." as a pen name. She interested herself in the cause of the Indians. A Century of Dishonor, appearing in 1881, was a sharp rap on the United States government for not taking better care of the natives. In 1884 her best story, Ramona, appeared. The scene is laid in California, It has been called "The Uncle Tom's Cabin" of the Indians. It was intended by the writer to attract public attention to the injustice suffered by the Indians. It won fame for the writer and still ranks as one of the greater American tales. She wrote several other novels and made many contributions to periodicals; but Ramona and a number of lovely lyrics are her title to fame. Some of the latter, as September and October, are sure to be found in every volume of children's verse.

Jacob's Ladder plant

The Jacob's Ladder is a familiar garden plant of the phlox family. The stem is erect, from one to three feet high. The name is derived from the regular order in which nine to twenty-one leaflets are arranged on the long leaf stem. The stamens and style are exserted beyond a bright blue, bell-shaped corolla. In the northeastern part of the United States, the species is found wild only on mountains and in swamps, but it is abundant in the meadows of the Rocky Mountains and far northward.

The Jacob's Ladder plant is also known as Charity.

The Jacob's Ladder plant is also known as Charity.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

What is homeostasis?

Homeostasis is the ability of an organism to maintain a stable condition within its body. This stable infernal environment is regulated by such body processes as respiration, circulation, and balance of body fluids. The nervous system and the hor¬mones (chemicals) of the endocrine system (gland system) greatly influence homeostasis. All living things main¬tain some balance of internal conditions.

Scientists believe that homeostasis indicates the degree of evolution (gradual development) of a species.

The steadier an organism's internal systems, the more independent it is of the external environment. In turn, the more independent it is of its external environment, the more highly developed it is.

Scientists believe that homeostasis indicates the degree of evolution (gradual development) of a species.

The steadier an organism's internal systems, the more independent it is of the external environment. In turn, the more independent it is of its external environment, the more highly developed it is.

Ships of the Vikings

When the Europeans of the 9th century prayed to the Lord "From the wrath of the Norsemen . . . deliver us," they had good reason to pray. The Norsemen, or Vikings, as they are often called, sailed out of the harbors of Scandinavia in their swift longboats for some two centuries. Their purpose was to raid and rob the richer lands to the south and southeast.

The Vikings were as good sailors as they were shipbuilders. Their drakkar was a longboat with a dragon on its prow and a large decorated single sail. Some 16 oarsmen sat on either side of the ship helping it to move through the waters from the coast of England as far south as Spain and Italy. The drakkar's "sister" ship was the snekkar, a somewhat larger boat with a snake as a figurehead on the prow.

The Vikings' raids took them to the British Isles where they succeeded in settling forces at the mouth of the Thames River. From this and other bases they sent forces to raid London, Paris, and Dublin. They left a permanent memorial in France where the region of Normandy takes its name from the Normans, or Norsemen, raiders and settlers of old. More distant voyages took these hardy sailors to Iceland, Greenland, and, in about the year 1000, to North America. Halfway round the globe Viking traders could be found sailing south along the rivers of Russia to trade their fur and amber for the silver, spices, and brocades of the region.

The Vikings were as good sailors as they were shipbuilders. Their drakkar was a longboat with a dragon on its prow and a large decorated single sail. Some 16 oarsmen sat on either side of the ship helping it to move through the waters from the coast of England as far south as Spain and Italy. The drakkar's "sister" ship was the snekkar, a somewhat larger boat with a snake as a figurehead on the prow.

The Vikings' raids took them to the British Isles where they succeeded in settling forces at the mouth of the Thames River. From this and other bases they sent forces to raid London, Paris, and Dublin. They left a permanent memorial in France where the region of Normandy takes its name from the Normans, or Norsemen, raiders and settlers of old. More distant voyages took these hardy sailors to Iceland, Greenland, and, in about the year 1000, to North America. Halfway round the globe Viking traders could be found sailing south along the rivers of Russia to trade their fur and amber for the silver, spices, and brocades of the region.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

What is a frieze?

Frieze, strictly speaking, is that part of the entablature of a building which forms a band between the architrave and the cornice, but more freely used to designate the decoration applied to that portion. The decoration varies with the order of architecture. In Doric examples it is divided into equal sections by raised portions with three angular flutes. The fluted sections are called triglyphs, the spaces between, metopes. The metopes are sometimes left plain, and sometimes—as in the Parthenon—richly decorated. In Roman buildings the decoration frequently takes the form of oxskulls and wreaths. When not so divided, the ornament often offers a continuous design, some¬times of men and animals, illustrating some theme, oftentimes floral. Familiarly, in domestic architecture, the word frieze is applied to the band of decoration just below the cornice of an interior.

Ionic frieze

How Did The Vikings Discover America?

Among the Viking explorers was a man who was nicknamed Eric the Red because of his red hair and beard. Eric grew up in Iceland, where his father had been sent as punishment for having killed another Viking. Eric had a terrible temper, and one day he killed one of his neighbors in a fight. The Vikings declared him an outlaw and ordered him to leave Iceland for 3 years.

Eric, his family, and friends loaded their possessions on board 25 ships and sailed away. Other Vikings told them about a large island to the west, so they headed in that direction. Eventually they landed on the rugged coast of this island. Although it was mostly icy wasteland, Eric called it Greenland. He hoped the name would attract settlers, which it did.

A Viking settlement was started around A.D. 985. It lasted for about 400 years.

Eric had a son who was named Leif Ericson—also known as Leif the Lucky. Leif, too, was an explorer. Around the year 1 000, Leif and his crew were caught in a storm while sailing from Norway to Greenland. For many days they were lost at sea. At last they sighted land—the coast of North America.

No one is sure where Leif and his men first came ashore. It may have been as far north as Labrador in present-day Canada or as far south as Virginia. The Vikings described the place as being covered by vast forests, wheat fields, and grapevines. They called it Vinland, or Wineland. Other expeditions followed and settlements were built. However, the Indians later drove out the Vikings. But the fact remains that the Vikings discovered America 500 years before Columbus.

Eric, his family, and friends loaded their possessions on board 25 ships and sailed away. Other Vikings told them about a large island to the west, so they headed in that direction. Eventually they landed on the rugged coast of this island. Although it was mostly icy wasteland, Eric called it Greenland. He hoped the name would attract settlers, which it did.

A Viking settlement was started around A.D. 985. It lasted for about 400 years.

Eric had a son who was named Leif Ericson—also known as Leif the Lucky. Leif, too, was an explorer. Around the year 1 000, Leif and his crew were caught in a storm while sailing from Norway to Greenland. For many days they were lost at sea. At last they sighted land—the coast of North America.

No one is sure where Leif and his men first came ashore. It may have been as far north as Labrador in present-day Canada or as far south as Virginia. The Vikings described the place as being covered by vast forests, wheat fields, and grapevines. They called it Vinland, or Wineland. Other expeditions followed and settlements were built. However, the Indians later drove out the Vikings. But the fact remains that the Vikings discovered America 500 years before Columbus.

John Suckling

Sir John Suckling (1609-1642), was an English Cavalier poet, born in Whitton, Middlesex, and educated at Trinity College, Cam¬bridge University. On the death of his father in 1627 he became heir to large estates. In the next year Suckling began an extended tour of the Continent, and in 1631-32 served with the forces of the Swedish king Gustavus II in defense of the Protestant cause. In 1641 he took an active part in the abortive plot to rescue Sir Thomas Wentworth, the pro-Royalist Earl of Stafford, from the Tower of London, in which he had been imprisoned at the time of the Great Rebellion. As a result of his complicity in the plot, Suckling was forced to flee to the Continent. Impoverished and in despair, he is said to have poisoned himself in Paris in the summer of 1642.

Suckling's works, few of which were published during his lifetime, were collected under the title Fragmenta Aurea ("Golden Fragments". 1646). The volume contains three plays. Aglaura (1637), The Goblins (1638), and Brennoralt, or the Discontented Colonel (1639); a theological tract titled An Account of Religion by Reason; and miscellaneous poems. In a later edition (1658) appeared an unfinished tragedy, The Sad One. Suckling's fame depends entirely upon his lyrics, which are distinguished for their grace and gaiety.

Suckling's works, few of which were published during his lifetime, were collected under the title Fragmenta Aurea ("Golden Fragments". 1646). The volume contains three plays. Aglaura (1637), The Goblins (1638), and Brennoralt, or the Discontented Colonel (1639); a theological tract titled An Account of Religion by Reason; and miscellaneous poems. In a later edition (1658) appeared an unfinished tragedy, The Sad One. Suckling's fame depends entirely upon his lyrics, which are distinguished for their grace and gaiety.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

What is a waterbed?

| waterbed |

Monday, April 23, 2012

What is Jaundice?

Jaundice is a yellow color of the skin and eye. It arises from coloring matter in the skin which the liver, whose province it is, has failed to remove. As one whose liver is out of order is not likely to look on the world with a pleased eye, the term "jaundiced" has been applied proverbially to one who is out of sorts.

All seems infected that th' infected spy,

As all looks yellow to the jaundic'd eye.

—Pope, Essay on Criticism.

Agustin de Iturbide

|

| Iturbide |

Agustin de Iturbide (1783-1824) was an emperor of Mexico. He was a native of Valladolid, Mexico. His father was a Spanish nobleman, his mother a rich creole. When the Mexicans first attempted to throw off Spanish rule the Spanish viceroy put Iturbide in command of the militia; but, instead of putting down the rebellion, Iturbide carried the militia over to the Mexican side. In 1822 the Mexicans made him their emperor and passed a law providing that his son should succeed him. The new emperor was too despotic, however, to suit the Mexicans, or perhaps they chafed under any autocratic government. In less than a year Iturbide was banished and went to Leghorn, Italy, to reside, with a pension from the Mexican Congress of $25,000 a year. A few months later Iturbide went to London. In 1824 he sailed for Mexico to recover his lost sovereignty. He landed July 14, and issued a proclamation that he would govern in accordance with the constitution and usages of England. July 17 he was arrested, and July 19 he was shot as a disturber of the public peace. The Mexicans settled a pension on his family.

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Thomas Sully

|

| Decatur by Thomas Sully |

Saturday, April 21, 2012

What is the Society of Friends?

|

| Colonial Quakers |

The "Green Revolution"

As a result of intensive research, scientists in the 1960's discovered ways of producing seeds that yielded much more rice and wheat than ever before. The new seeds were also improved by the use of better fertilizers and by advances in the techniques of irrigation.

The ability to feed large numbers of people became increasingly critical as the world's population grew (currently stands at 7 billion). Unfortunately, most of the fastest-growing countries were also the poorest and the least able to feed themselves. In the 1980's, for example, Ethiopia was unable to cope with the long period of drought and famine that plagued the country, and millions of people starved to death.

The ability to feed large numbers of people became increasingly critical as the world's population grew (currently stands at 7 billion). Unfortunately, most of the fastest-growing countries were also the poorest and the least able to feed themselves. In the 1980's, for example, Ethiopia was unable to cope with the long period of drought and famine that plagued the country, and millions of people starved to death.

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Where is Ithaca (Odyssey) located?

Ithaca is one of the Ionian Islands, situated west of Greece and east of Cephalonia, from which it is separated by a narrow channel. Its area is about 38 square miles, the surface being mountainous and the coast steep and rocky. Vineyards and olive and other orchards cover the mountain sides. Fishing is carried on by the inhabitants, another industry being the production of olive oil. Its population is about 3,040 (2001).

Ithaca is supposed to be the site of the castle of Ulysses, the principal character in Homer's Odyssey. Excavations were made by Schliemann in 1869, which corroborated sites named by Homer.

Ithaca is supposed to be the site of the castle of Ulysses, the principal character in Homer's Odyssey. Excavations were made by Schliemann in 1869, which corroborated sites named by Homer.

Ulysses

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

What is a Jack-o'-Lantern?

Jack-o'-Lantern is a lantern carried by children, especially after nightfall Hallowe'en. It is made from a pumpkin by cutting holes to represent a mouth, nose, and eyes. A candle placed within gives a peculiarly weird light. The name is also applied to the Will-o'-the-wisp,or ignis fatuus.

Jack-ó-Lantern

Jade mineral

|

| Jade nephrite |

Jade was used by prehistoric races for ornaments, weapons, and various utensils, specimens of which have been found among the relies of the lake-dwellers of Switzerland, and of other primitive peoples. It is believed that the Jade was brought to Europe, however, as it is not found native to that country, but in the Far East. The best-known locality for jade is eastern Turkestan. The Chinese and Japanese use it largely for carved vases and bowls, for boxes and for various kinds of jewelry. They also use it in making implements.

The word jade is from the Spanish and is part of a phrase meaning "stone of the side," so named because of a belief that this mineral would cure pain in the side, or colic.

Water Colors

Water Colors are pigments prepared for the use of artists and others by mixing coloring substances in the state of fine powder with a soluble gum such as gum arabic. These are made up in the form of small cakes, which are rubbed down with water and applied with a brush to paper, ivory, and some other materials. Moist water colors are made up with honey or glycerin as well as gum, and are prepared so as to be kept in small earthenware pans or metal lie tubes. Dry cakes require to be rubbed down with water on a glazed earthenware palette or slab, but moist colors can be mixed with water for use by the friction of a brush, so that the japanned lid of the box which contains them serves for a palette. The latter are accordingly very convenient for sketching from nature.

In water-color painting two methods are employed; by one the artist works in transparent colors, by the other in opaque or body colors. In working by the latter method, which somewhat resembles on painting in its nature, Chinese white is mixed with light colors to give them body. Not only is there much artistic work done solely in transparent colors, but it is almost always these that are used for tinting mechanical drawings, maps, and the like. Some artists freely combine transparent, semi-transparent, and opaque colors. The quick drying of the water-color pigments is favorable to rapid execution; and greater clearness is attained than is practicable in oils. In water-color painting the texture of the paper employed is often of importance. Water-color drawings are of course more easily injured by damp than oil paint¬ing.

In water-color painting two methods are employed; by one the artist works in transparent colors, by the other in opaque or body colors. In working by the latter method, which somewhat resembles on painting in its nature, Chinese white is mixed with light colors to give them body. Not only is there much artistic work done solely in transparent colors, but it is almost always these that are used for tinting mechanical drawings, maps, and the like. Some artists freely combine transparent, semi-transparent, and opaque colors. The quick drying of the water-color pigments is favorable to rapid execution; and greater clearness is attained than is practicable in oils. In water-color painting the texture of the paper employed is often of importance. Water-color drawings are of course more easily injured by damp than oil paint¬ing.

Monday, April 16, 2012

Waterproof Materials

Waterproof Materials are any substances used to prevent infiltration of water or (inaccurately) other liquids. Typical waterproofing materials, all having commercial uses, are tar, oils, rubber, asbestos, asphalt, oil paints, aluminum hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxes, paraffin, resin, varnish, and cellophane.

Tar is used for caulking wooden boats and for waterproofing ropes, roofs, tarpaulins, and roads. Asbestos is likewise used for roofs, and asphalt has similar uses for roads. Asphalt varnishes are also used for protecting iron from weathering. Oils are used both as film in protecting machinery from water vapor and in impregnating fab¬rica, as raincoat cloth, instrument cases, and oiled shoes. Oils are also the solvent in most paints and bind the particles of pigment into a thin, resistant layer. Rubber may be used in sheet form as a cover, but it is usually vulcanized to a fabric, which gives the rubber durability, or it is deposited by electro-chemical means into the pores of the fabric. Any water-insoluble substance may be used in place of rubber, in such connection, providing it can be conveniently precipitated. Such substances are aluminium hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxe», paraffin, resin, asphalt, tar, and varnish. To make fabrics impervious to water and at the same time to allow for ventilation, recourse is had to waterproofing the yarn and then weaving the fabric out of this yarn. An important addition to the family of waterproof materials is cellophane, a cellulose product from which umbrellas, wrappings and raincoats are made.

Read more »

Tar is used for caulking wooden boats and for waterproofing ropes, roofs, tarpaulins, and roads. Asbestos is likewise used for roofs, and asphalt has similar uses for roads. Asphalt varnishes are also used for protecting iron from weathering. Oils are used both as film in protecting machinery from water vapor and in impregnating fab¬rica, as raincoat cloth, instrument cases, and oiled shoes. Oils are also the solvent in most paints and bind the particles of pigment into a thin, resistant layer. Rubber may be used in sheet form as a cover, but it is usually vulcanized to a fabric, which gives the rubber durability, or it is deposited by electro-chemical means into the pores of the fabric. Any water-insoluble substance may be used in place of rubber, in such connection, providing it can be conveniently precipitated. Such substances are aluminium hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxe», paraffin, resin, asphalt, tar, and varnish. To make fabrics impervious to water and at the same time to allow for ventilation, recourse is had to waterproofing the yarn and then weaving the fabric out of this yarn. An important addition to the family of waterproof materials is cellophane, a cellulose product from which umbrellas, wrappings and raincoats are made.

Read more »

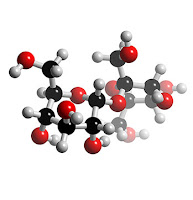

What is sucrose?

Sucrose, or saccharose, is a sugar, C12H22O11, which, together with lactose and maltose, belongs to the important group of carbohydrates known as disaccharides. It is soluble in water, slightly soluble in alcohol and ether-, moderately soluble in dilute alcohol, and crystallizes in long, slender needles. Sucrose is dextrorotatory, rotating the plane of polarized light to the right. Upon hydrolysis, it yields a mixture of glucose and fructose, which are levorotatory, turning the plane of polarized light to the left. Thus the mixture obtained is known as invert sugar, and the process is known as inversion. Inver¬sion is carried on in the human intestine through the aid of the enzymes invertase and sucrase, metabolism of Sucrose is extracted chiefly from sugar cane and sugar beet, and is commonly called "cane sugar". When heated to temperatures above 180 °C. (356 °F.), sucrose becomes an amorphous, brown, syrupy substance called "caramel", which is used as a coloring matter in baking.

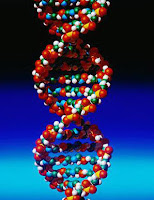

Genetic research

In 1962 the Nobel Prize in medicine, the most honored scientific award in the world, was given to an American and two British scientists. What they had discovered, in the 1950's, was the structure of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), an essential component of genes. As you already know, genes are the small units of chromosomes that convey characteristics, such as color of hair and eyes, from parent to child. By understanding DNA, one can understand how a gene is structured—what scientists Call the "genetic code."

By unraveling the genetic code, the experimenters with DNA came closer to explaining how different life forms are created. This break-through made possible new research into viruses, bacteria, human cells, and diseases such as cancer. Scientists found it possible to reproduce life forms in the laboratory. Major advances in treating illness were anticipated.

By unraveling the genetic code, the experimenters with DNA came closer to explaining how different life forms are created. This break-through made possible new research into viruses, bacteria, human cells, and diseases such as cancer. Scientists found it possible to reproduce life forms in the laboratory. Major advances in treating illness were anticipated.

Sunday, April 15, 2012

What is a Water Mark?

Water Mark, in ordinary language, the mark or limit of the rise of a flood; the mark indicating the rise and fall of the tide. In paper making, any distinguishing device or devices indelibly stamped in the substance of a sheet of paper while yet in a damp or pulpy condition. The device representing the water mark is stamped in the fine wire gauze of the mold itself. The design is engraved on a block. from which an electrotype impression is taken; a matrix, or mold, is similarly formed from this. These are subsequently mounted on blocks of lead or gutta-percha to enable them to withstand the necessary pressure and serve as a cameo and intaglio die, between which the sheet of wire gauze is placed to receive an impression in a stamping press. The water marks used by the earlier paper makers have given names to several of the present standard sizes of paper, as pot, foolscap, crown, elephant, fan, post.

Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart (1337-1405) was a French chronicler, born in Valenciennes. At the age of 18 he went to England, where he spent a year under the patronage of Philippa of Hainault, his countrywoman. At the age of 20 Froissart began to write his history; and having completed the first section, he began his travels (1361-1366). Returning to England, he made an excursion into Scotland about 1364. Froissart accompanied the Black Prince to Dax, and the Duke of Clarence to his marriage at Milan. He was appointed in 1369 to the cure of Lestines. In 1395 he once more visited England. In 1372 Froissart began to write his famous Chroniques, which describe events in western Europe from 1326 to 1400. It is not entirely reliable from an historical point of view, but it presents a picture of the time is unrivaled in its vivid color and its charm.

Jewellery - some facts

Jewellery, or jewelry, refers to the costly personal ornaments of gold, silver, enameled ware, and the like, usually adorned with precious stones. As produced today it consists chiefly of ma-chine-made articles, often beautiful in design but lacking the artistic touch seen in the handmade ornaments of ancient and medieval times. Of late years such schools as Pratt Institute, New York, whose students in the department of fine arts have produced very beautiful hand-made Jewellery, have done much to revive the art of Jewellery making. This is a commendable step, for its proficiency in the art of making Jewellery is a test of a nation's artistic development. A jeweler must produce the largest amount of beauty within the smallest space.

The use of jewellery is as old as civilization. Some of the ancient Egyptian work resembled greatly the Chinese cloisonne of today; that of the ancient Greeks was notable for its purity and simplicity; while that of the old Romans was more ostentatious but of less exquisite workmanship. The Renaissance produced masters in Jewellery-making as it did masters in every other art. Foremost among these great jewelers were Benvenuto Cellini and Albrecht Dürer.

The modern period is characterized by a simpler and more graceful method in mounting gems and in the designing of jewelry. During the nineteenth century the diamond was the stone in high favor; now it has made way for the pearl. For many years the jewelers of London and Paris, and the gem-cutters of Holland held first place, but now American workers have won a name abroad. The quantity of gaudy Jewellery sold today is an unfortunate reflection on popular taste. Nothing bespeaks poorer judgment as to the eternal fitness of things than the wearing of such spurious jewelry, unless it be expensive jewelry worn out of place.

The use of jewellery is as old as civilization. Some of the ancient Egyptian work resembled greatly the Chinese cloisonne of today; that of the ancient Greeks was notable for its purity and simplicity; while that of the old Romans was more ostentatious but of less exquisite workmanship. The Renaissance produced masters in Jewellery-making as it did masters in every other art. Foremost among these great jewelers were Benvenuto Cellini and Albrecht Dürer.

The modern period is characterized by a simpler and more graceful method in mounting gems and in the designing of jewelry. During the nineteenth century the diamond was the stone in high favor; now it has made way for the pearl. For many years the jewelers of London and Paris, and the gem-cutters of Holland held first place, but now American workers have won a name abroad. The quantity of gaudy Jewellery sold today is an unfortunate reflection on popular taste. Nothing bespeaks poorer judgment as to the eternal fitness of things than the wearing of such spurious jewelry, unless it be expensive jewelry worn out of place.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

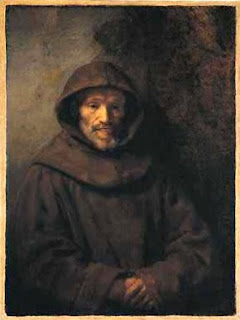

What is a friar?

Friar is the popular distinguishing title of the members of the mendicant orders. The first friars were the Franciscans or Grey Friars and Dominicans or Black Friars. To these were added the Carmelites or White Friars by Innocent IV (1224), and the Augustinian hermits or Austin Friars by Alexander IV (1256). In the 15th century the Serviles and Trinitarians or Crutched Friars were granted the same privileges as the four mendicant orders.

Franciscan friar

The Jacobin club

Jacobin is a name applied to a revolutionary club of France, and later to the party favoring democracy. When the National Assembly first met in Versailles, Lafayette, Mirabeau, and a few other Liberals formed a society known as the Friends of the Constitution. After the assembly removed to Paris, the name was changed to Jacobin club, because of their meeting in the library of the church of St. James. After the removal to Paris, the character of the club changed rapidly, the moderates dropped out, the number of members increased, and the name became synonymous with the party of extreme democracy. Daughter societies were formed throughout France, dependent on the mother club at Paris. At first the Jacobins had little influence in the assemblies though they were all powerful with the mob, but as the Revolution progressed they became more and more dominant. The Jacobins directed the attack upon the Tuilleries in 1792; they initiated the September massacres; they were the ones who insisted that Louis must die. Later when France was beset by foreign war and internal disaffection, the Jacobins instituted the Terror, which, hideous as it was, seemed a necessary evil at this time. Cruel as the Jacobin policy often was, it forms a striking contrast to the wavering vacillation of the Girondists. Every one rejoiced when in 1794 the Jacobin organization was finally suppressed after the repulsion of the foreign dangers and the downfall of Robespierre, yet it is difficult to see how otherwise the same results could have been accomplished. As Lowell says,

"They did as they were taught, not theirs the blame

If those who scattered fire brands reaped the flame."

Suite (music)

A suite, or partita, is the earliest type of musical composition containing a series of discrete sections, or movements. The suite was developed in the 16th century as a series of dance tunes, usually composed in one key.

These tunes were so arranged as to present strong contrasts between slow and fast tempos and dignified and gay moods. The four basic movements of the classical suite are: the allemande (Fr., "German"), a quiet dance in moderate tempo, composed in common time; the courante (French, "running"), a lively dance, often complex in its rhythms; the sarabande, a stately dance of Spanish origin in triple time, rich in harmonic embellishment; and the jig or gigue, a rapid and lively dance, also in triple time. A prelude, not derived from any dance form, was later customarily included at the beginning of the suite, and one or more additional dance forms, such as the minuet, gavotte, bourrée, chaconne, and passacaglia, were also sometimes inserted, generally between the saraband and gigue. The classical suite reached its perfection in the examples by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. In the 18th and 19th centuries the classical suite gradually merged with and was superseded by the sonata. Modern compositions called suites are only loosely related to the original form; they are primarily symphonic works, characterized by considerable freedom of structure and tonality, and cast either in abstract forms or in greatly modified dance forms.

These tunes were so arranged as to present strong contrasts between slow and fast tempos and dignified and gay moods. The four basic movements of the classical suite are: the allemande (Fr., "German"), a quiet dance in moderate tempo, composed in common time; the courante (French, "running"), a lively dance, often complex in its rhythms; the sarabande, a stately dance of Spanish origin in triple time, rich in harmonic embellishment; and the jig or gigue, a rapid and lively dance, also in triple time. A prelude, not derived from any dance form, was later customarily included at the beginning of the suite, and one or more additional dance forms, such as the minuet, gavotte, bourrée, chaconne, and passacaglia, were also sometimes inserted, generally between the saraband and gigue. The classical suite reached its perfection in the examples by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. In the 18th and 19th centuries the classical suite gradually merged with and was superseded by the sonata. Modern compositions called suites are only loosely related to the original form; they are primarily symphonic works, characterized by considerable freedom of structure and tonality, and cast either in abstract forms or in greatly modified dance forms.

Laser applications

In 1960 a device called a laser was invented. It could store energy and release it all at once in an intense beam of light. This beam remained straight, narrow, and very concentrated, even after it had traveled millions of miles. Its uses were extraordinarily varied—a perfect example of the combination of scientific discovery and engineering applications. Lasers were used in surgery to weld damaged tissue in the eye, to burn away skin growths, and to repair decayed parts of teeth. They were used to measure distances. A mirror placed on the moon by the Americans who landed there allowed scientists to calculate the distance to the moon more accurately than ever before.

Lasers helped engineers make tunnels and pipelines straight. They enabled manufacturers to cut precisely into hard substances, such as diamonds. Lasers also transmitted radio, television, and telephone signals. They made it possible to show three-dimensional pictures on a television or film screen. Thus one invention had effects in dozens of activities.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Freyr and Freyja, Norse gods

FREYR, or FREY, is the Norse god of rain, fertility, and peace, was, like his sister Freyja and his father Njord, a survival from the pre-Odinic mythology. His festival was at the winter solstice (Christmas). A well-known saga relates his wooing of Gerda, daughter of the frost-giant Gymir.

FREYJA is the Norse goddess of the spring, love, and fertility, sister to the god Freyr. She was often confused, and in later times identified, with the goddess-mother Frigga, the wife of Odin.

Freyr

FREYJA is the Norse goddess of the spring, love, and fertility, sister to the god Freyr. She was often confused, and in later times identified, with the goddess-mother Frigga, the wife of Odin.

Freyja

Jackstones game

Jackstones (also called jacks, fivestones, jackrocks, onesies, knucklebones, or snobs) is a game played by one or more persons with from one to five small pebbles or bits of iron. Regular iron jackstones have six knobbed prongs. The game may be played in several ways. There is tossing and catching in all of them. The five stones may be held in the palm of the hand and thrown up together and caught on the back of íhe hand. The jack may be tossed up and caught alternately on the palm and the back of the hand, the player counting five for each successful catch. The player who reaches the highest score wins. Sometimes four stones are laid on the ground. The player losses the jack and catches it, picking up a stone from the ground each time, while the jack is in the air. This method may be varied by holding the four stones in the hand and laying one on the ground between each toss and catch. Sometimes the jackstones are laid in a pile. The player arranges them in a figure, as the four corners of a square or in a straight line, this between tosses.

Lake Superior

|

| Lake Superior |

Read more »

Thursday, April 12, 2012

What is a harelip?

A Harelip is a cleft (split) through the upper lip. It is called harelip because it looks like the hare's lip, which is split. Doctors do not know what causes harelip. Something prevents this section of the lip from growing together before the baby is born. Harelip may be single; that is, only one side of a lip may be cleft. Or both sides of a lip may be open. Cleft palate, an opening in the roof of the mouth, often occurs with harelip. Sometimes a deformity of the nose also occurs. Doctors can successfully close these openings by means of surgical operations.

Sir William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (1852-1916) was a Scottish chemist who, with Baron Rayleigh, isolated the first rare atmospheric gas, argon. Ramsay also discovered the other inert gases: helium, neon, krypton, and xenon. For this work, he received the 1904 Nobel prize for chemistry. His explanation of me nature of these elements led to important ideas about atomic structure. The gases also have great practical importance.

Ramsay was born in Glasgow and studied in Germany at Heidelberg and Tübingen universities. He taught at Glasgow and Bristol, and at University College in London. He was knighted in 1902, and in 1911, he became president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Ramsay was born in Glasgow and studied in Germany at Heidelberg and Tübingen universities. He taught at Glasgow and Bristol, and at University College in London. He was knighted in 1902, and in 1911, he became president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Plastics, the first synthetic substances

The first synthetic substances—substances that do not occur in nature—were developed by chemists in laboratories in the 1800's. A few of these sub¬stances began to have wide applications. For example, celluloid was used to make movie films, and bakelite was used for electrical equipment. It was not until after 1945, however, that these substances, called plastics, began to appear in every area of life. By the mid-1960's, for example, there was more synthetic rubber than natural rubber in the world.

Plastics became an essential part of daily existence. They were used to equip and furnish kitchens. They changed the way buildings were constructed and affected the manufacture of objects from toys to cars. They completely altered the appearance as well as the manufacture of most of the things people use every day, from tooth-brushes to telephones. Synthetic fibers were woven into easy-care fabrics for clothing, upholstery, and many other uses.

Many plastics were made from oil products. The production of plastics, therefore, depended on the unpredictable nature of international oil prices. Nevertheless, plastics continued to be essential to modern life in the 21th century.

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

What are territorial waters?

Territorial Waters are those waters which fall under the jurisdiction of a state. Rivers or lakes wholly within the boundary of a state are the property of that state. If a body of water forms a boundary between two countries, each owns half of such body, i. e., up to the middle of the part which serves such a function. If, however, such waters serve as a connecting link between parts of the high seas, they are submitted to international arbitration for jurisdic¬tion, as in the case of the Panama Canal. Although international law does not make definite ruling to cover those uninclosed waters near the border of a country, it is generally recognized that such a country may extend its jurisdiction out as far as 3 miles. Thus the civil and criminal laws of a country are enforced over all ships both national and foreign in this strip.

The Frogs (Aristophanes)

|

| The Frogs representation |

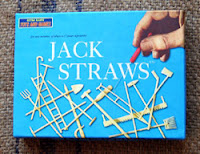

Jack Straws game

Jack Straws is a familiar parlor game. It is played with straws or with strips of bamboo, wood, ivory, bone, or the like. The straws are tumbled in a confused heap on a table. The players take turns. The first withdraws straws, one at a time, as long as he can do so without joggling the heap or moving any other straw. The right to play then passes to the next. The player who has the most straws at the conclusion of the game wins.

The pieces may be withdrawn with the finger or angled for with a hook provided for the purpose.

The pieces may be withdrawn with the finger or angled for with a hook provided for the purpose.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a canal 103 miles long (in¬cluding 4 miles of approach channels), which crosses the Isthmus of Suez and connects Port Said on the Mediterranean Sea with Suez on the Red Sea. The Egyptian king, Rameses II, seems to have been the first to excavate a canal between the Nile delta and the Red Sea. This, having been allowed to fill up and become disused, was reopened by Darius I of Persia. It was once more cleared and made serviceable for the passage of boats by the Arab conquerors of Egypt. The French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps set himself, in 1849, to study the isthmus thoroughly, and in 1854 he managed to enlist the interest of Said Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, in his scheme for connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. Two years later the Porte granted its permission and the Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal was formed, receiving important concessions from the ruler of Egypt.

Read more »

Read more »

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Computers of today

|

| Pascal calculating machine |

In the 1600's, the French scientist Blaise Pascal had invented a machine that could perform arithmetical calculations. The idea intrigued scientists and engineers for the next 300 years. However, the necessary machinery was too large and cumbersome to have many applications.

It was not until the 1950's that machines capable of storing and processing information quickly and compactly were developed. These computers rapidly made an impact on society and were improved from year to year. They not only operated ever more quickly, but they required a smaller and smaller amount of space to store gigantic amounts of information.

By the mid-1980's computers performed many varied functions. They guided the flights of spacecraft and recorded every airline reservation in the world. They drew maps, kept accounts, and printed newspapers. Computers also played games with children, controlled the flow of fuel to a car's engine and solved complex mathematical questions. Problems in every field could be tackled that would have been considered impossible 60 years earlier.

What is a water thermometer?

The Water Thermometer is an instrument in which water is substituted for mercury, for ascertaining the precise degree of temperature at which water attains its maximum density. This is at 39.2 °F., or 4 °C., and from that point downward to 32 °F., or 0 °C., or the freezing point, it expands, and it also expands from the same point upward to 212 °F., or 100 °C., or the boiling point.

|

| Hot water thermometers |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)